NEAT Fighter A NEAT Project in AI (in Minecraft)

Video

Project Summary

The goal of our project is to train a Minecraft agent to fight in a 1v1 gladiatorial scenario. We would like our bots to learn to kill the opposing agent and avoid being killed, through evolution. We are using a Neuroevolution algorithm, which is a form of machine learning that uses genetic algorithms to evolve the structure and edge-weights of neural networks. More specifically, we are using the NeuroEvolution of Augmenting Topologies (NEAT) algorithm which was created by Ken Stanley in 2002 while he was at The University of Texas Austin.

Each bot is a Minecraft agent with certain “DNA” that specifies its “brain”: a neural net which has percepts as inputs and actions as outputs. It uses its neural net at every tick to determine what actions to take. At the end of each episode, we evaluate how well a given fighter performed by computing a fitness function, which takes into account the damage inflicted on the other agent, the damage received, as well as distance to the other agent. After each generation, selected bots mutate and breed to generate the next generation.

At the writing of our previous report, we had been able to train 1 bot to fight and kill a stationary enemy. Now we have fully expanded to train bots to fight each other. We were pleasantly surprised by how well this final phase of the project turned out, as the basic methodology we used previously gave good results without much tweaking. We also observed fascinating emergent behavior when watching the training of our project, like evolutionary arms races. We were really pumped to have done this project, and super satisfied with the way it turned out.

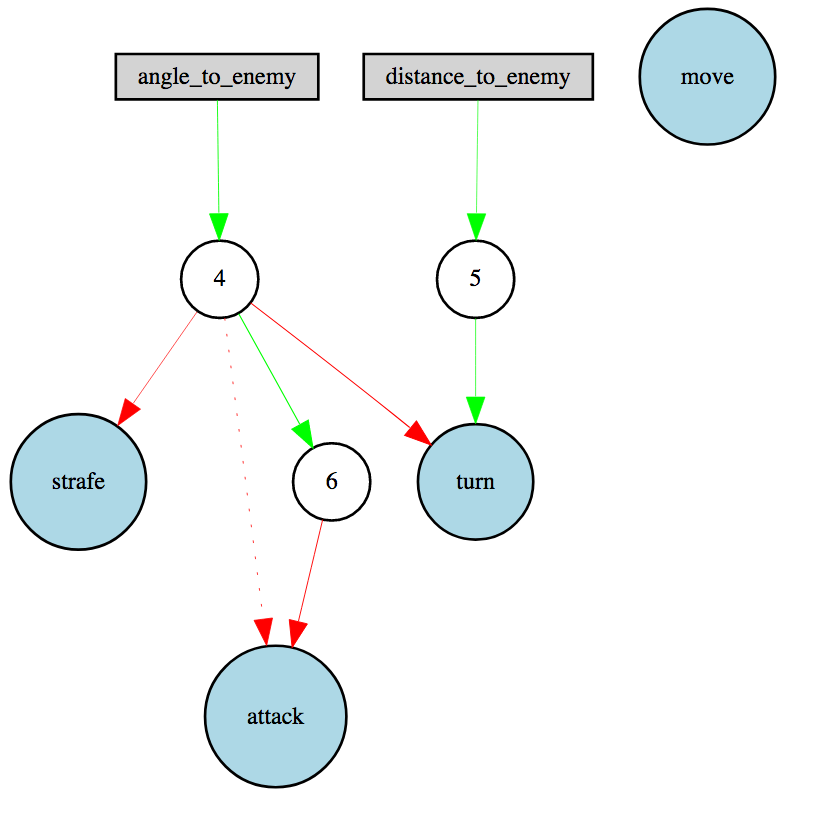

An example neural net of one of our later-generation bots

Context

As stated before, the NEAT algorithm is a type of genetic algorithm created by Ken Stanley which changes its weight parameters based on the fitness and the diversity among the specimen of each generation by tracking the history. Although this field of “neuroevolution” (evolving the parameters of a neural net through a genetic, evolutionary algorithm) is old and dates back further than this paper, NEAT introduced the idea of “species” in the population.

The idea of speciation is highly motivated by biological analogues. Essentially, Stanley, et al. wanted to pursue the biological concept of sexual reproduction and chromosome crossover (where two successful genomes are combined to create a new, hopefully successful genome). However, this concept proved difficult to implement for neuroevolution, since two equally-successful neural nets may have radically different structures, such that chromosome crossover is nonsensical and results in an unsuccessful offspring. Previous solutions were just to give up on implementing this biologically analogous crossover by only implementing asexual reproduction, or to have the neural net’s structure predetermined as a hyperparameter. But Stanley did not give up. Ken Stanley is a hardworking, persevering researcher, and he (et al.) came up with this idea of speciation - in which genomes in the population are grouped together into species, by a similarity metric. Only organisms within the same species are selected to mate with each other.

Approaches

High Level

Before we get into the nitty gritty, we just want to give a quick overview of the different aspects of our approach:

-

Environment - the arena and our map that we will be training the agents in

-

Training Procedure - how we train our agents, and specifics of the NEAT algorithm

-

Fitness - what our fitness function takes into consideration and its importance in the bigger picture of the NEAT algorithm

-

1v1 Testing Procedure - how we dealt with new problems with training bots against other bots

Environment

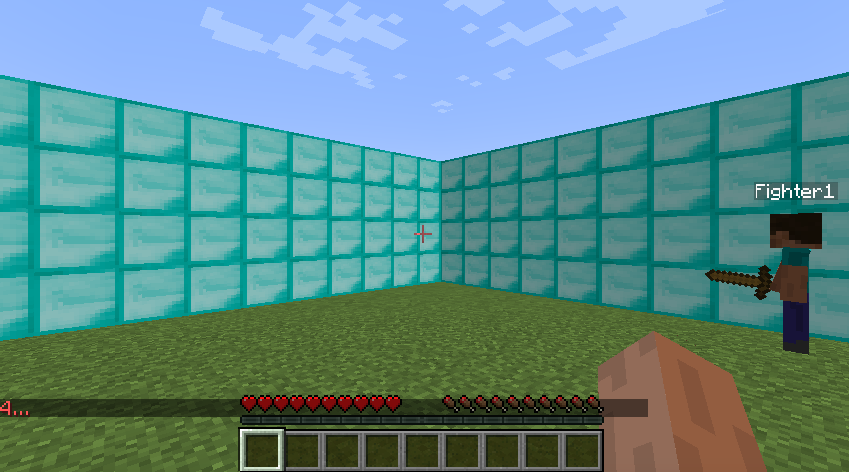

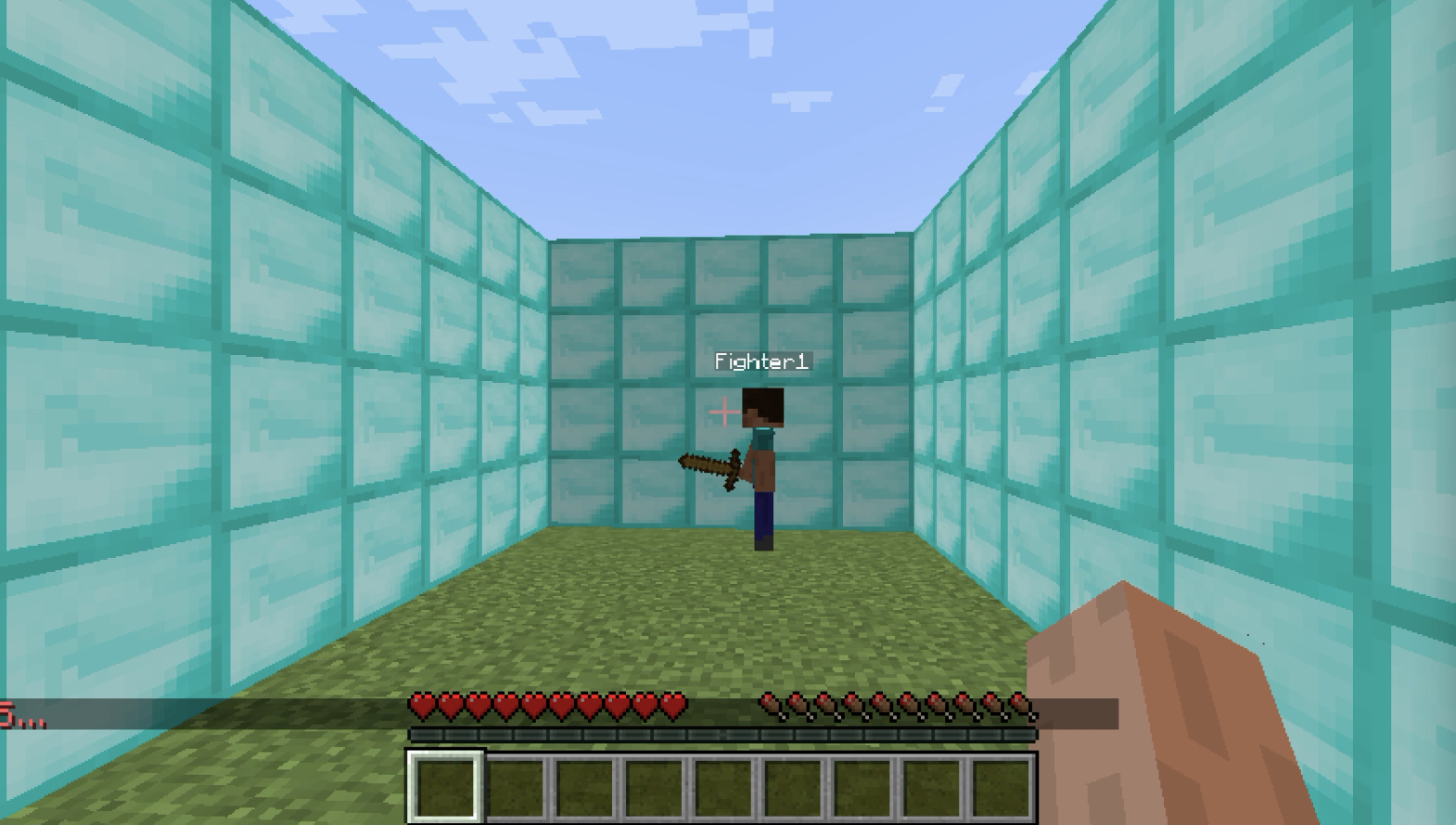

Environment setup: We created our world using Project Malmo. We tried running our project on different sized worlds with different setups.

- 10x10x4 Diamond Block Arena, No Armor: This was our initial approach. We hypothesized that if we give our agent a big enough arena, then over multiple generations, we could see clearly if our agent is learning or not.

- 10x5x4 Diamond Block Enclosure, No Armor: This was the second iteration of our environment. We wanted to test out different arenas to see how greatly it would affect our agent. Our hypothesis was: the smaller the arena, the faster the agent would first randomly hit the opponent. Which in turn would result in a better agent after the course of multiple generations.

- 10x5x4 Diamond Block Enclosure, with Armor: Again we tried making our area smaller for the same reasons stated above.

Our results after comparing across final generations did not prove our hypothesis. There was no obvious direct correlation between the size of the area and how well our final generation performed. It should be stated that this was only true at our full-scale testing.

Training Procedure

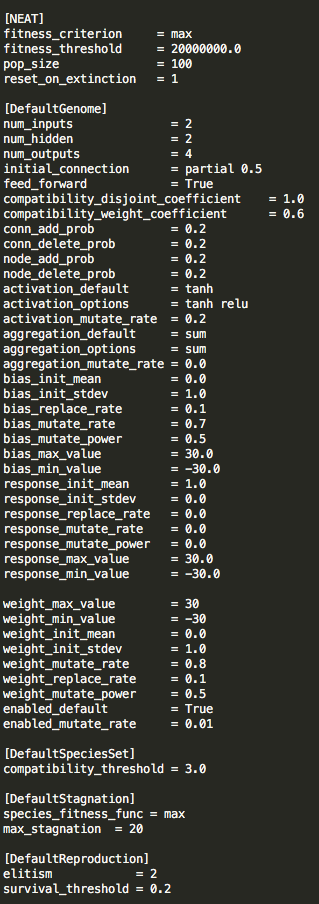

Our fighter class can make four continuous moves: move (forward/backward), strafe (left/right), turn (left/right), and attack (true/false). It decides these commands based on the neural net’s output. There are two inputs to the neural net: the agent’s distance to the other agent, and the agent’s angle to the other agent. The outputs of the neural net will also be a continous variable bounded by the tanh function which will be a value in the range [-1, 1] (discussed further in details in the NEAT configuration section). Each continous variable for move, strafe, turn will output the speed at which the agent will move. An example for move: a value of 1 will make the agent move forward at full speed while -1 will make the agent move backwards at full speed. The agent will stop if that variable is 0. This decision to map the output to action is one that we did not come up with lightly. We have tested other methods of mapping but have choosen this for its simplicity. If we had more time, this is what we would like to test and maybe change to see if it will help produce a better result. For the attack action, anything above 0 will be mapped to 1 and anything less will be mapped to 0. In other words, the agent will only attack if the neural net output is greater than 0.

Scaling our input features is also an important aspect in making sure our neural net is sensical. For the tanh function, anything below -1 and above 1 will be mapped to -1 and 1 respectively. Hence if our input feature is anything that is not within this boundary, it will lose its meaning. For example, the distance 5 and 10 will practically equal to each other as that input in the eyes of the neural net will be mapped to 1. Therefore, it is important we use the full range of continous variable between -1 and 1.

def run(self):

agent_state_input = self._get_agent_state_input()

scaled_state_input = scale_state_inputs(agent_state_input)

output = self.neural.activate(scaled_state_input)

self.agent.sendCommand("move {}".format(output[0]))

self.agent.sendCommand("strafe {}".format(output[1]))

self.agent.sendCommand("turn {}".format(output[2]))

self.agent.sendCommand("attack {}".format(0 if output[3] <= 0 else 1))

Fitness

For each genome, we calculate its fitness or how well it does by taking into considering the following results: mission time, inflicted damage, distance to the other player over time, and damage taken. We want to punish a bot for taking longer to kill, because we favor a species that kill the other opponent as fast as possible. We also want to highly reward inflicting damage on the other agent and highly punish taking damage. Lastly, as a means to encourage early-generation species to get closer to the other agent, we included the distance in our fitness where the distance area over a period of time will be subtracted from the overall fitness (kind of like training wheels to reward our kids to at least get close to each other when they’ve not yet learned to brutally murder each other). In order words, a species that consistently spends its time closer to the other agent will have a smaller distance area hence the punishment will be less.

For each of the variable that we are taking in consideration for our fitness function, it is multiplied by a scaling factor in order to make sure that there is a logical ordering of importance. In our current settings, we rate the importance of the variables in the following way of highest to lowest: inflicted damage, damage taken, mission time, and distance area.

INFLICTED_DAMAGE_SCALE = 2

DAMAGE_TAKEN_SCALE = INFLICTED_DAMAGE_SCALE * 0.90

TIME_SCALE = 0.01

DISTANCE_SCALE = 0.01

The reasoning behind this ordering is that we want our agent to fight and deal as much damage as possible. An agent who can deal damage should always be favored over one that does not. Second, we favor agent who takes the least damage. The scale for mission time and distance is equal to each other. However, in the earlier generation, mission time will not play much of a role because no one will be able to kill each other.In those cases, distance will be more of a factor in the final fitness relative to the rest of the generation’s popuation. We can also assume that if an agent is consistently dealing damage, its distance is also consistently closer to that of the other agent. Hence our final fitness is computed as follows:

def GetFitness(self):

return self.inflicted_damage * INFLICTED_DAMAGE_SCALE - (self.mission_time * TIME_SCALE) - (DISTANCE_SCALE * self.distance_area) - (DAMAGE_TAKEN_SCALE * self.damage_taken)

In the NEAT algorithm, the methodology behind how each genome is assigned its fitness score is arguably the most important aspect. In any given generation, the fitness function tells the NEAT algorithm how well did that specific genome do relative to the rest of the generations. We want a fitness function that will implicitly model how well each genome did compare to others without running them together. This is a problem that we encounter later on when we attempt to pair two different genome against each other which is discussed in later sections. Going back to the point, our fitness function may not be the best but it gave us good results in a 12 hour training session but were we, hypothetically, to use a better and more comprehensive fitness function to evaluate the genomes, our result couldve been achieve is much shorter time or that an extreme good genome could have dominated.

These calculated values are then passed to AgentResult which we use as our fitness function. This assigns a fitness to each genome by giving it a scaled reward for inflicting damage and punishes the agent for elapsed time and the distance between the agent and the enemy.

1v1 Testing Procedure: Pairing The Bots

For each arena battle, we have two agents running simutaneously fighting against each other. The problem of correctly pairing up different genomes is not a trivial one. In fact, our initial strategy was to have the same genome fight against itself. However, this does not really encourage the overall goal of this project, which is to produce a fighter who can fight against anyone. If we paired a genome against itself, we were implicity encouraging certain strategy that will only work against itself. In other words, we need to pit our agents against other agents. The next strategy that we attempted was to just simply randomly pair up any given two genome and have them fight against each other. This also posed another problem, in that this method would result in too much noise. Noise would force our training session to take longer because it would take longer for a genome to dominate as it would have alot of variance. Similar to that of the problem in fitness, we would not be correctly representing how a genome did in respect to the rest of its generation, but only versus a random enemy. Hence there is this problem, where we do not want too much variance but we also want just enough to produce a fighter that would do well against all types of behavior.

The solution we came up with is that we run each generation’s genome against the previous’s generation’s best. In fact, this also introduces a behavior that closely model that of biological evolution in the real world. To further explain, after running each generation, we will save the best genome which we will call the baseline genome of that generation and we will use the baseline to fight against the next generation. This type of method preserves the relative ordering of fitnesses within each generation in that in a given generation everyone will be running against the same fighter. Our baseline genome for generation-1 is one that doesn’t make any action and simply just stands still. The interesting behavior that we observe is that the generation’s baseline often switches between a fighter that is very aggressive and one that is defensive. This make sense as if the baseline is very aggressive, that generation’s best will be a fighter that can defend well and vice versa. Following Stanley’s tradition of biological analogues, this type of behavior is close to that of predator and prey in nature, as predators are often equipped with offensive trait while prey is good at defending its life. This type of method, we hope, will generate a species that is balanced between offensive and defensive. Again, the NEAT algorithm is highly stochastic and thus may generate species that fluctuate in strategy and fitness, just like animals and plants floating through the winds of time in nature on Earth - the beautiful planet that we call home.

NEAT Configuration

Our config-fighter file has all the configuration for the NEAT algorithms parameters. We used a population size of 100 with two inputs (relative angle to the enemy and distance) and one hidden input. As of current, we are using relu for our activation function but there are other options available to fine tune the learning process. The neat-python library allows us to specify mutation rate, probabilities of adding or removing an edge or node, aggregation in the neural nets, and much more.

Evaluation

While evaluating our project was fairly simple in the previous phase (we simply kept track of the fitness of the bots of each generation over time at slaying the static enemy), it was much, much harder to evaluate our project while doing gladiator fights. The fitnesses of our training no longer can be compared across generations, since all the bots of generation 2 fight against a different enemy than the bots of generation 3.

Qualitatively, we can simply watch each generation of our project while training, and it’s clear that the successive generations learn to kill others. But quantitatively, we have no existing recourse for evaluating.

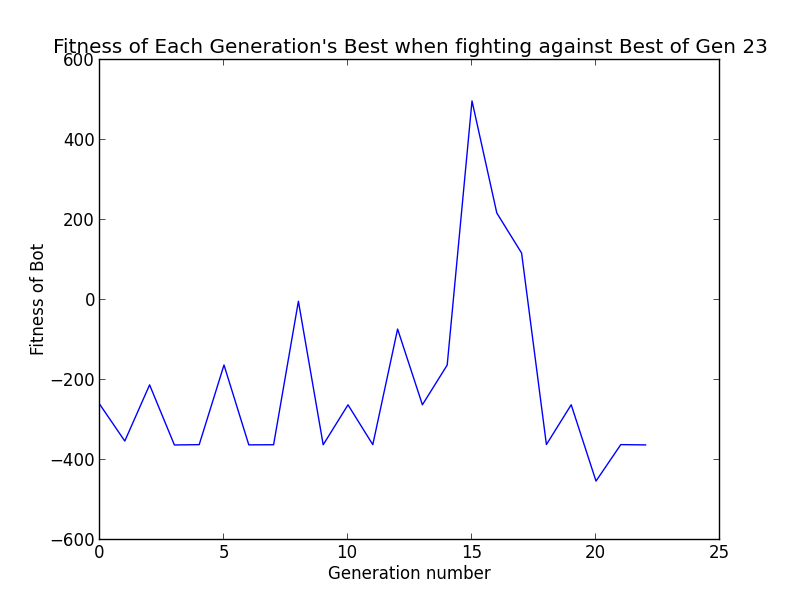

Thus, to evaluate our project now, we came up with an entirely new process which we perform after training completes. During training, we save the genomes of the highest-fitness bot of each generation. Then, after training, we pit the highest-fitness bot of each generation against the highest-fitness bot of the final generation (who we’ll refer to as Spartacus). We’ll save the fitness score of each of these bots when they fight against Spartacus, and then graph them. If the fitness score has an upward trend, we can conclude that each generation is evolving to become better at fighting.

Evaluating 1v1 fighting is still fraught with caveats, however. For instance, can we actually even objectively measure the fitness of a bot? Sure, a bot might be good at fighting a certain other bot, or even against fighting all bots, but our presupposed goal of creating “the best bot at gladiator fights” is, in reality, treacherously ambiguous. Do we want a bot that has the highest winrate versus all other bots we’ve created? The best bot in the final generation? Although, through our multiple testing runs, the Spartacuses were often a great and had high winrates, it’s theoretically possible that there would exist some rock-paper-scissors cycle of bot strategies. Furthermore, there is some stochasticity in the fights themselves, since each Malmo tick and Minecraft tick aren’t precisely controlled. Thus, the same bots fighting multiple times will not always give the same result.

Even so, the graphs that we made through this methodology supported our qualitative observations that the bots evolved well.

In our graph, we can see that most bots lost to this run’s Spartacus, confirming that the bot by the end has learned to kill, since they have fitness values less than 0. Generations 15, 16, and 17 defeated Spartacus (perhaps indicative that these 3 generations form a “scissors” class to Spartacus’s “paper”, and 18’s “rock”, but this is just speculation).

Conclusion

We had a lot of fun doing this project. We learned a lot about neuroevolution, and will feel comfortable in the future using this method of reinforcement learning for other problems that might otherwise be intractable with traditional reinforcement learning. It was very exciting to watch each generation of bots improve (and plateau) at fighting, and we highly recommend doing a similar project if you enjoy watching things learn. All in all, this was a fantastic project and I personally would give our experience an A+. We would all give our project experience 10 stars out of 10, “would research again”.